Post 12. April 2016

22.4.16

Post 11. April 2016

17.4.16

Post 10. April 2016

09.4.16

Post 9. March 2016

23.3.16

Post 8. March 2016

21.3.16

Post 7. February 2016

22.4.16

Post 11. April 2016

17.4.16

Post 10. April 2016

09.4.16

Post 9. March 2016

23.3.16

Post 8. March 2016

21.3.16

Post 7. February 2016

28.2.16

In the Studio: New Painting For Retake

Today was

the first day of really good light in the studio and initial preparations were

made on the large final painting for Retake Reinvent. Capitalising on the

geometry inherent in Jones' work, this painting includes the superimposed

rotation on an extended horizontal format. In this respect it follows the large

drawing shown at CAM contemporary, Casoria, Naples last December and allows a

compositional structure closer to my approach to pictorial space yet referencing

the centralized geometry inherent in the Jones.

Post 6. November 2015

The first series of paintings have been photographed.

Post 5.

Studio June to September 2015

For this post I will describe the visual

considerations that have transpired over the intervening months of working in

the studio. I was concerned with the compelling composition of Building in

Naples and why this and the others of the Naples series have a quality that

stays in the mind and imprints a visual template on one’s consciousness. I want

to get as close as possible to Jones’s visual thinking; to interact with his

mind - as much as such a thing is possible. What happens with these paintings

(as happens with all great painting) is that there is a characteristic of

continuity. The view from the window is there for our eyes to stare at; its

nothing really special. An everyday urban rooftop, with notable landmarks but

present only by chance. Each time we look it is familiar but different. The

drying cloths have moved or the light has changed even though it is the same

time of day or perhaps the trees are moving in the breeze. Buildings in Naples

and the others from the series are paintings that exist outside of their own place

and time; they have that quality of continuity that is something to do with

underlying structure. As if the content of the painting has always existed and

will do beyond the present. In an essay, Philip Guston talks about the

condition of form, and I believe the same condition is present in Jones’ Naples

series (1).

The non-static image. In order to attempt to get

closer to the underlying structure of the painting various strategies have been

employed. These include drawing and simple exercises like making grids on photocopies

and digital image manipulation. It seemed the one way to bring the distance

between my perception of the subject and the way Jones was interpreting what he

saw, was to look at the compositional elements of the painting. I think this is

something to do with trying to get closer to understanding Jones’ methodology. First

I drew a grid like form over the main structural points on one of the photocopies

of the painting.

These structures included the edge of the walls

(verticals) and tops of parapets (horizontals). It became apparent immediately

that what I had been observing in a non-objective way was in fact a geometric

order. The main vertical and horizontal lines in the central sections of the

painting formed a near-square vertical rectangle.

Moreover, the parallels were at equal distance. Surely

then, this geometry and symmetry would create a dull and static image? With my

modern understanding of composition the centralisation of image and focal point

(even using the square canvas) might in the least be problematic for an image

that relies on contrast for any kind of dynamic. In almost a split second my

preconceptions are dashed.

Jones probably would have used a perspectival device

for the construction of space. He would have been highly familiar with classical

landscape painting and the spatial configuration of figure and object

(architecture) within a perspectival framework. I wonder if Jones whilst in

Italy was following Alberti’s system ‘construzione legittima’ where two diagrammatic

drawings are combined into one. Perhaps he was following Brunelleschi’s

methodology utilising a square viewfinder, later called a ‘perspecteur’ as used

by Millet and Degas. With contemporaries, Wilson and Reynolds (Head of the

Royal Academy) the modern methods of perspective would have been engaged with. Reynolds

called for the Enlightened artist to engage with the “true idea of beauty” (2).

Looking at the sketchbooks made by Jones whilst in Naples I had the impression

that they were formulaic. This was evident in the mark being made; a consistent

single pencil line with tonal value often absent as if working from a prescribed

visual plane akin to photography where much of the optical reality is ready

flattened onto a surface. I am not suggesting that Jones was using any form of

projection rather that a frame device with lines like a ‘perspecteur’ was used

to select the image in question. His method was to look, select and analyse. I

think though, Jones was searching for an image; perhaps an ideal image. Rather

than setting out on an exploratory way of drawing, he set about an empirical study

of the visual world around him looking for the right image.

Moreover, in drawing the grids onto the photocopy of Buildings

in Naples, I realised that the symmetry went beyond the square and parallel

lines and included the whole pictorial space by locating itself directly in the

centre of the painting’s rectangular space. We have then a central vertical

bang in the centre of the painting. These strong verticals, pilaster strips on

the face of the building equally spaced with the edge of the main wall catching

the light exactly in the centre of the painting defy conventions of modern

composition. How often in modern painting do we eschew symmetry and equal proportion,

preferring an element to be off-centre or slightly unbalanced in order to create

composition through contrasting form? Mondrian worked with parallels and

verticals with contrasting areas as interval; Albers and Riley use utilise

geometry and repetition of geo metric form (including the square) yet in these

examples, I would argue in order to prioritise the agenda of colour as main pictorial

concern. This is for a further essay later. Here, Jones has gone for the geometric

centre of the painting as the main focal point; the washing curling in the wind

almost exactly in the centre of the painting.

Before long, further enquiry into symmetry included

the rotation of the image and superimposition. This led to a development for a

pictorial space that seemed to emphasise further geometries of the painting by

creating through superimpositions of the roof through the long wall, an angular

form with a direction toward the right and left edge of the painting and most

significantly rectangular frames around the distant dome and parapet with a

line running directly over the top of the parapet walls. The alignment of form

seemed never ending!

I resolved to work with this new photographic image;

it seemed to give me a compositional structure that was closer to my idea of

pictorial composition by creating a dynamic between flatness and (retaining) perspectival

distance and allowing space to move across the entire surface of the painting. How

was it then, with all of the symmetry and geometry that the Jones painting does

not look contrived? Quite the opposite actually and its commanding spread of

space seems natural and real. Further drawings developed as I mulled over these

new discoveries and I resolved to make first a large drawing (110 x180cm) in

mixed media to get right into the spaces and intervals of the composition. In making

the large mixed media drawing and working to get elements and forms in the

right place with lines intersecting and the distant dome not too close to the

central line and so on, I realised that the compositional agenda for Jones was

an essential part of his enquiry; he searched for the right image and had

developed an eye for close analysis of the everyday to recognise and realise form.

(1)“ Having gone thus far in our inverstigation of the

great stile in painting, if we now should suppose that the artist has formed the

true idea of beauty, which enables him to give works a correct and perfect

design; if we should suppose also that he has acquired a knowledge of the

unadulterated habits of nature, which gives him simplicity; the rest of his

task is, perhaps, less than is generally imagined. Beauty and simplicity have

so great a share in the composition of a great stile, that he who has acquired

them has little else to learn”.

Discourse III (p.49). Discources on Art. Sir Joshua

Reynolds. Ed Wark, R.Robert. Yale 1981.

(2) “It’s important to take detours because you come back

to the main road with much greater intensity. My only interest in painting is really,

as I go on and on, just only this interest, on this metaphysical plane where

the condition exists of no finish, no end, but infinite continuity. That is, the

distributions of forms are in a condition which gives you the feeling that

there was a structure unseen previous

to what you see. Now, this pause gives promise to future structures never

finished, always looking as if they’re going to avoid this total immobility.” On

Piero della Francesca (p.141). Philip Guston. Collected Writings Lecture and Conversations.

Ed. Coolrodge, Clark. University of California Press 2011.

Post 4. 30.06.15

Reflecting on Context 1

|

Buildings in Naples, with the North-East Side of the Castel Nuovo. 1782.

Oil on Italian Made ‘Dutch’ laid writing paper 22.2 x 29.1 cm.

Collection: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

|

In reflecting on my Jones painting

Buildings in Naples, whilst making the first series of study paintings I have

been intrigued by the commanding presence of the main wall section with white

cloths hanging, in half profile stretching back towards trees and that makes

for the whole content of the painting. I have been working to get as close to

the painting as I can, its structure, visual meaning and dynamic; it is a very

challenging process and I am aware of the distance still yet to go. The

thinking behind Buildings in Naples is not one I am familiar with. There is an

underlying geometry to the painting, a method of constructing the pictorial

space that is very different to the way I work. That is to say, I have a perhaps

relatively unrestricted way of drawing; the painting for me has an autonomy

from the beginning. This I suppose is a very modern way of working; one aligns

the development of an image with the imagination and process of making. The

painting has to speak back; one area of blue has to work with another area of a

different hue, and so forth. The construction of the image is therefore predominantly

linked to the operation of colour, the main instinctive driving force, with recognition

playing a major role. This process though seems removed from the Jones and so I

need to explore further what it is then that is so compelling about the series

of small Naples paintings.

Buildings in Naples is one of the series that Jones painted from the roof of the building in which he had an apartment and these were only painted very shortly before he left after living there for some time and made in a very short space of time. Perhaps making some last minute paintings of the place he had been living but certainly having subconsciously digested the roof top vistas as visually engaging and deciding or finally having time to act on the stimuli. In any case, these series of small paintings of the rooftops, walls and windows are the paintings that speak to us as being very modern, crossing the two centuries of art history to locate themselves right up to date in the treatment of abstract shape, form and colour (1). In these Naples paintings it is their quiet, still, motionless understatement that is so compelling. Simple yet austere and commanding of the eye, I wonder if Jones really thought of these as more than studies, the subject being unconventional and perhaps even unworthy in his time. In being painted from the rooftop and looking straight across at eye level, the ground or base of the building is omitted from the paintings thus eliminating foreground and directly emphasising the flatness of the painting in that the forms of walls travel to the pictorial edges, left, right and bottom. In a Wall in Naples (1782 National Gallery London) (2) this is pushed even further with the left wall behind and on the top edge of the painting above a dark window and rectangle of blue across the top to the right edge. This new way of looking and constructing an image was unprecedented (3) at the time with studies and drawings of buildings (in Italy particularly) when concentrated on buildings and rooftops, they tend to be from a mouse eye view. With Jones it is straight on, thus giving us a flatness of plane readable through our early twenty first century eyes as belonging to a more recent past, to the painting of the latter half of the twentieth century perhaps; flat certainly, but not in a Modernism sense per se, but moreover in terms of geometry, spatial planes across the surface and penetrating the pictorial plane with perspective interval. The sky areas, as in Wall in Naples, become part of this spatial organisation. Jones’ visual selection of walls, crumbling surfaces and open void windows presents us with an unexpected leap into the language of contemporary painting.

|

WA1954.81 Thomas Jones, Rooftops in Naples, oil on paper, mounted as a drawing, 1782

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

|

Buildings in Naples is one of the series that Jones painted from the roof of the building in which he had an apartment and these were only painted very shortly before he left after living there for some time and made in a very short space of time. Perhaps making some last minute paintings of the place he had been living but certainly having subconsciously digested the roof top vistas as visually engaging and deciding or finally having time to act on the stimuli. In any case, these series of small paintings of the rooftops, walls and windows are the paintings that speak to us as being very modern, crossing the two centuries of art history to locate themselves right up to date in the treatment of abstract shape, form and colour (1). In these Naples paintings it is their quiet, still, motionless understatement that is so compelling. Simple yet austere and commanding of the eye, I wonder if Jones really thought of these as more than studies, the subject being unconventional and perhaps even unworthy in his time. In being painted from the rooftop and looking straight across at eye level, the ground or base of the building is omitted from the paintings thus eliminating foreground and directly emphasising the flatness of the painting in that the forms of walls travel to the pictorial edges, left, right and bottom. In a Wall in Naples (1782 National Gallery London) (2) this is pushed even further with the left wall behind and on the top edge of the painting above a dark window and rectangle of blue across the top to the right edge. This new way of looking and constructing an image was unprecedented (3) at the time with studies and drawings of buildings (in Italy particularly) when concentrated on buildings and rooftops, they tend to be from a mouse eye view. With Jones it is straight on, thus giving us a flatness of plane readable through our early twenty first century eyes as belonging to a more recent past, to the painting of the latter half of the twentieth century perhaps; flat certainly, but not in a Modernism sense per se, but moreover in terms of geometry, spatial planes across the surface and penetrating the pictorial plane with perspective interval. The sky areas, as in Wall in Naples, become part of this spatial organisation. Jones’ visual selection of walls, crumbling surfaces and open void windows presents us with an unexpected leap into the language of contemporary painting.

Jones trained for a time

under Richard Wilson when the established painter was working on a number of

classical Grand Style compositions selecting subjective motifs for an ideal or

metaphysical painting yet progressively linking Welsh and classical elements (4). However,

Wilson also encouraged working plein-air,

a relatively new way of information gathering; the artist works in the

landscape directly in front and experiential of the location as a way of

understanding landscape through studies but also as a method to produce

sketches and finished compositions with a naturalistic reality in their own

right. In Thomas Jones An Artist

Rediscovered (5) are reproductions of two landscape studies by Jones that seem more to relate to

the context of naturalistic landscape painting of the Netherlands cc.1780, than

the classical ideal.

|

| Left. Thomas Jones. View of a River on Outskirts of Town 1768 present location unknown. Right Thomas Jones. View of a Canal on Outskirts of Town 1768 present location unknown. |

Moreover, in the work made in

Wales around Pencerrig and the Carneddau shortly before the departure for

Italy, that a precursor to the identification of visual form in the Naples

paintings is evident. In Carneddau, from Pencerrig c1775, spatial areas of

light fall at intervals on the fields and in the colour of trees, turning

autumnal brown-orange with low cloud interacting with the horizon, that there

is a desire for the real that is specific and closely observed – from nature.

|

Thomas Jones. Carneddau Mountains from Pencerrig

c.1776

Oil on paper on canvas, 29.5 x 51 cm

Collection: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

|

In the related Field near

Pencerrig, looking northwest to Gorllwyn, a ruined building is included on the

far left with dark window recess again a precursor the Naples paintings and

indicating Jones’s predilection for buildings, albeit in this instance as part

of a compositional device rather than total subject.

|

Thomas Jones. Field near Pencerrig

1776

Oil on paper, 23 x 30.5 cm

Collection: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

|

Lawrence Gowing in his

definitive essay on Jones discusses the Pencerrrig paintings of 1772 (four

years before the ones I mention but not unrelated in my mind) and defines

Jones’s process:

“The theatre of ideal

landscape, for all its enlightenment, was like a prison. In the little scenes

at Pencerrig it is all gone. ….Instead there are tones and shapes that were

apparently directly matched with a judgement that remains phenomenal; it is so

entirely his own, with no hint of conventional formulation. ……At a second look

we realise that this artist is alert and attuned to certain alignments, angles which are repeated (6).

Forward to my Jones panting. It is then the structure of the image that needs to be closely looked at. There is a precision and geometry about the Naples series that adds to the compelling totality of the image; the walls, rooftops and spaces are clearly defined and absolutely relational. I note that examination with infra red light of my Jones painting Buildings in Naples, has revealed extensive pencil underdrawing, sketching in principle the architectural forms (7). I am now going to return to the painting itself and deconstruct its geometry as the next stage of my encounter with this paradoxically distant yet so near modern artist.

Forward to my Jones panting. It is then the structure of the image that needs to be closely looked at. There is a precision and geometry about the Naples series that adds to the compelling totality of the image; the walls, rooftops and spaces are clearly defined and absolutely relational. I note that examination with infra red light of my Jones painting Buildings in Naples, has revealed extensive pencil underdrawing, sketching in principle the architectural forms (7). I am now going to return to the painting itself and deconstruct its geometry as the next stage of my encounter with this paradoxically distant yet so near modern artist.

1. "If this sketch had been the only example of Jones’s work to have survived, so that it had to be judged in isolation, it would not be easy to place: and would anyone have ventured to date it as early as 1782?”Gere, John. Apollo. June 1970. Thomas Jones An Artist Rediscovered. Sumner, Ann Smith, Gred (eds) Yale University Press and National Museums and Galleries of Wales, p 13.

2. http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/a-wall-in-naples-114194

3. Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819) View of the Porta del Popolo, Rome. 1782. Oil on paper. Musee du Louvre. This work has been cited as relational to Jones but I consider it does not have the same focus or intensity. Riopelle, Christopher 2003 Thomas Jones in Italy. Thomas Jones An Artist Rediscovered. Sumner, Ann Smith, Gred (eds) Yale University Press and National Museums and Galleries of Wales, p 55.

4. Richard Wilson The Lake of Nemi with Dolbadarn Castle (Diana and Callisto). http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/diana-and-callisto-189270

5. Thomas Jones An Artist Rediscovered. Sumner, Ann Smith, Gred (eds) Yale University Press and National Museums and Galleries of Wales p. 32

6. Gowing Lawrence. The Originality of Thomas Jones. 1985 Thames and Hudson ; p18.

7. Thomas Jones An Artist Rediscovered. Sumner, Ann Smith, Gred (eds) Yale University Press and National Museums and Galleries of Wales p219

Video diary 3: 02 04 15

In

this third film of making the first series of studies after the Thomas Jones, we talk

about the painting of the walls and brushwork in Buildings in Naples and how this leads to forming layers

in the new paintings.

Video diary 2: 21 03 15

In this film I reflect on the perceived distance from Jones at this stage and on the usefulness of tracking the work in relation to the process of making.

Video diary 1: 22 02 - 13 03 15

Post 3 05.03.15

I have started a small series of study paintings in relation to my choice. These are on primed mdf board and I am working in oils. In fact these paintings were started last autumn certainly before my choice of exact painting had been made and probably not thinking about Retake at all. The sparse initial shapes were applied in response perhaps, to previous work and in trying to establish a pictorial space slightly random in hue and position; my usual way of commencing. Ones ideas for the painting that were taking place during the construction stage (the making of the stretcher) have evaporated by this stage and one is left with the proposition of blank canvas and starting an image.

These then were begun before and have been commandeered for

the task in hand, that is to make a new work from old and reinterpret the Jones

painting. So visually and directly, I have looked at the Jones by having an A3

print out in the studio and studied it over a number of days, mulling over its

form and construction. When I say study, really this means constantly noticing

it because where I have placed it I cannot avoid it and therefore keep finding

myself looking at it for some minutes; I must affirm here what a remarkable

painting it is. In looking I have been selecting actually, some shapes that

could be used incorporating them in the studies. However, and moreover, my series

of studies are a response to the Jones, not really just directly taking

elements but assimilating the sense of plane and shape through his marvellous description

of walls, shadow and light, and engaging with the kind of compositional

proposition that Jones is making and referring to this methodology in these

studies.

These then are the first images of the study paintings, my

initial creative statement in response to Buildings in Naples.

Post 2 - 27.02.15

On reflection about my final choice for the painting from which to focus on, I have come to a conclusion. All of the works I have seen so far have been considered and looked at, their visual criteria mulled over from the reproductions, photos and sketches I have. I am working with all of them because to get a rounded view of Jones’s working method I want to see all areas of his oeuvre: the grand landscapes in classical tradition; the landscapes from around Pencerrig, his sketchbooks and watercolours. I find myself thinking ‘is there a Jones in the gallery here’. Last Saturday I called into the National Gallery to have a look at the two Naples paintings they have there, both up on the gallery wall and one very familiar.[i]

However, I have been thinking about Buildings in Naples, and as this painting is now in the United States and will be until after the end of the project in 2016 it seems incomplete to use this painting even though it is the most famous. In January, I went to the excellent Constable exhibition at the V & A[ii]. This was a retrospective of John Constable and sort to explore all aspects of his process thoroughly. This it did and at all times emphasised his close observation of nature. Interestingly for this project were the direct copies that he had made from other artist’s works. These were less interpretive rather direct and close copies and really I could not fathom why these were being made and to what purpose. But, he taught and gave lectures and I am sure that these copies were his form of slides – images he could take along to illustrate his talk. No doubt, Constable was also learning from copying as we all do if we set out to even minutely copy every detail as we perceive them in a new work. But, I could not help feel that these of his, and I am the greatest fan of Constable, were rather dead end.

I digress. In the Constable show were three Jones paintings I recall. They were in a corner, rather blocked in I felt, in a room of Constable’s peers. Included in this selection was the view of Carneddau, from Pencerrig c.1775, with the staggering red orange tree in the centre right whose colour is fantastic. The painting however, that caught my eye was one that I had seen before but forgotten. Buildings in Naples, with the North-East Side of the Castel Nuovo 1782.

|

| (c) The National Museum of Wales / Amgueddfa Cymru |

This was an outstanding painting and the colour resonated across its surface with deep greens, greys and blues and ochres all in an orchestration of composition. I was so thrilled to see that it was one of the National Museum Cardiff collection paintings and therefore eligible for the project! It also is of a defined place in Naples. Rather than anonymous buildings and corners or walls this was an identifiable place that I might possibly visit for location work. This would be difficult for many of the Naples works as they were of course (and as is intrinsically part of their understated power) anonymous views of the backstreets, but this might be possible with two distinct spires and the corner of the Castel Nuovo and the roofline of the Palazzo Reale.

This then will be the main painting for the project:

Buildings in Naples, with the North-East Side of the Castel Nuovo. 1782.

Oil on Italian Made ‘Dutch’ laid writing paper 22.2 x 29.1 cm

Front cover of Thomas

Jones (1742-1803): An Artist Rediscovered Yale University Press 2003

Accessed 10 Jan. 15

Painting can be viewed here:

But this painting is in the United States until after the end of the project in November 2016! I would therefore look at the landscapes and the other Naples works that would be available plus the sketchbook from 1771 (to 1778) that the museum has and some works on paper. I was at this stage, still thinking that I would focus on that painting for the project despite not being able to see it. However, even then I was thinking that the first hand experiential analysis would be something not to miss and therefore went to NMC with an open mind.

In actual fact there were two unexpected surprises. Two

Naples paintings I had not seen before. The first, House and Tree with Versuvius

in the Background is a great little painting that does not seem to be online

but is on long term loan to NMC and would therefore be possible for the main focus

of my research. It consists of a square-ish wall facing the viewer straight on

with a striking curved arch window with behind a curved wall dropping down the

right hand side and leading from its right edge to an apparently curved wall;

curved from the top profile and in the tonal values of the surface; this wall

leads the eye back behind further foreground buildings that are in deep

greenish shadow. Further more in the close foreground there is a lower

rectangular wall with two different heights. It is a panting about shape and

the way Jones focuses on the sharp contrast between light wall and dark window

recess is profound. The darkened window hovers as a focal point of the painting

and it is located within the lower fifth of the painting!

In actual fact there were two unexpected surprises. Two

Naples paintings I had not seen before. The first, House and Tree with Versuvius

in the Background is a great little painting that does not seem to be online

but is on long term loan to NMC and would therefore be possible for the main focus

of my research. It consists of a square-ish wall facing the viewer straight on

with a striking curved arch window with behind a curved wall dropping down the

right hand side and leading from its right edge to an apparently curved wall;

curved from the top profile and in the tonal values of the surface; this wall

leads the eye back behind further foreground buildings that are in deep

greenish shadow. Further more in the close foreground there is a lower

rectangular wall with two different heights. It is a panting about shape and

the way Jones focuses on the sharp contrast between light wall and dark window

recess is profound. The darkened window hovers as a focal point of the painting

and it is located within the lower fifth of the painting! |

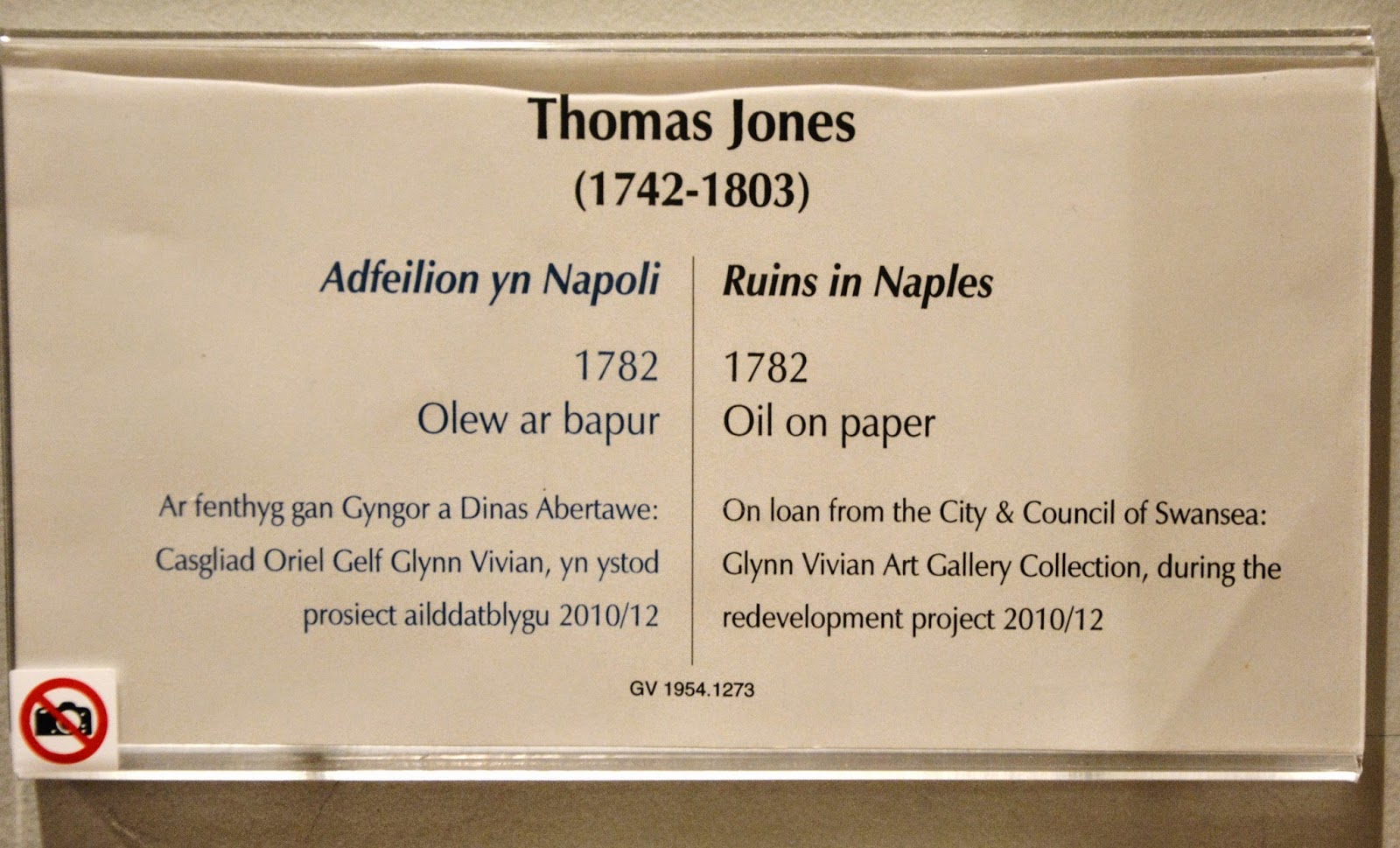

| City & County of Swansea: Glynn Vivian Art Gallery Collection |

This painting has a lot of potential for compositional

development consisting of a panorama of walls with different shapes and colour

areas, multiple windows and recesses and curved arches in fenestration across

the walls. The walls are seen over the top of trees and in the foreground a large

cave like structure, yet it is the character and physiognomy of the wall that

is the main content of the painting. Again, here is my thumbnail of the

painting made on the visit.

The Thomas Jones Sketchbook

Also on the visit I was also able to look at the sketchbook

of Thomas Jones from the 1770s (Jones bought the sketchbook in Rome on 29 March

1771). This was remarkably well preserved with pages certainly not looking 200

years old. I wonder if our current sketchbooks will appear in such good

condition down the line. The sketch ran for several years and contained many

mainly linear drawings of landscapes, buildings, trees and boats/sails. They

seemed specifically made as studies for possible further composition and the

way elements were put together suggested as if these plan like drawings could

be used in another process, perhaps mechanical, a camera lucida perhaps. This

requires further investigation. There were colour studies and notes for colour;

there were studies of buildings with light and tonal study. The overall

impression was of a formulaic way of analysing the landscape, each sketch with

a definite and precise purpose.

AS 10.01.15

No comments:

Post a Comment